Being able to cross the street is a fundamental requirement for anyone travelling in an urban area, and yet for pedestrians in many circumstances, this basic need is often either onerous or dangerous. Our road designs regularly require people to make difficult decisions between adding five minutes to their trip to reach a controlled crossing or taking the direct route that involves risky mixing with traffic. The evidence shows that far too often, people take the riskier option, and that tragically, many of these end in serious injury or death. It’s even more patronizing when the apparent road safety solution for this behaviour is campaigns that tell people to not “jaywalk”.

The Problem: Engineering Guidance

In Ontario (and much of North America), the current guidelines around midblock pedestrian crossings illustrate a classic catch-22: for a new crossing to be considered, there must already be a significant number of people crossing at that location. However, without a safe crossing, many individuals won’t risk it, even if it would be their preferred route.

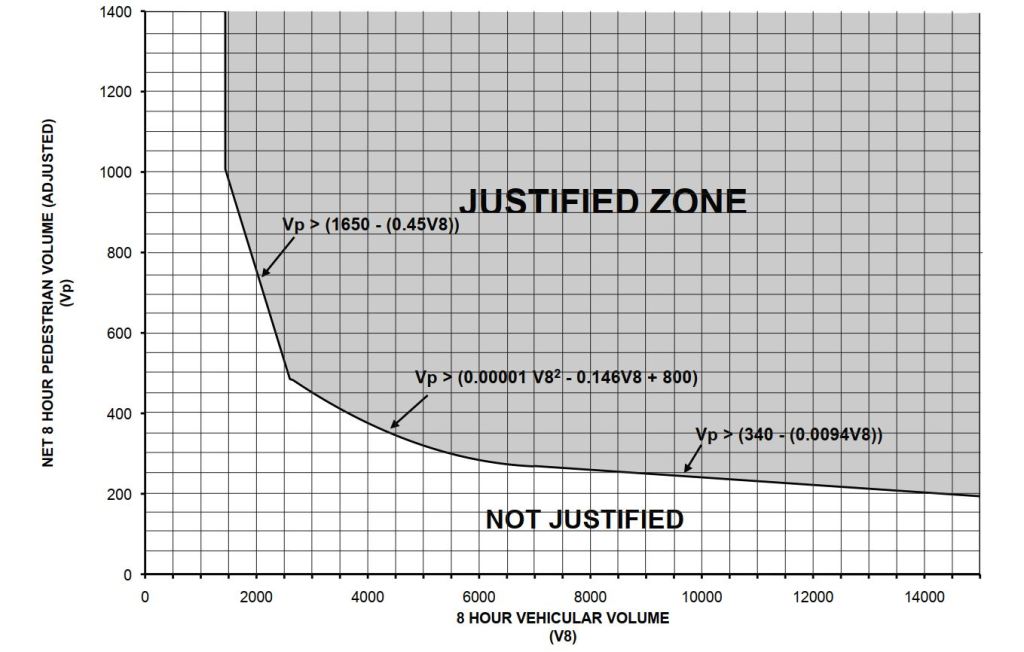

For a typical multi-lane arterial road carrying over 15,000 vehicles a day, Ontario’s traffic signal design guidance requires around 200 pedestrians crossing in an 8-hour period to justify a pedestrian signal – that’s an average of 25 pedestrians an hour entering a dangerous situation.

While these requirements partially stem from the need to spend public funds effectively, they are also significantly biased towards motor vehicle traffic and delay. The same guidance requires that all signals be spaced an absolute minimum of 215 metres apart (even though Canada’s national guidance[1] allows spacing as little as 100 metres), primarily because it allows back-to-back left turn lanes for cars at adjacent intersections. More so, the guidance recommends spacing signals even further, at 415 metres to 625 mtres for signal progression so that drivers on an arterial street to catch “green waves” between signals (even though evidence[2] shows that on congested urban arterial roads, adding signals can actually improve delay for cars). There is no equivalent guidance in the manual for the spacing of signals on the basis of enhancing pedestrian travel, safety, and connectivity.

It’s important to mention a this point that all of the above is guidance, and you’ll regularly find situations where signals were installed that didn’t meet these warrants or spacing requirements. But any situation requiring engineers to depart from established guidance can put them or the host municipality in a risky situation from a legal perspective, so there is a disincentive to doing so.

The Dillemma: Roads versus Streets

Here is the problem: Ontario’s traffic signal design guidance – and most other guidance documents in North America – is written for roads. Roads are routes designed to prioritize the movement of car traffic over long distances between places with minimal conflicts between modes. When designed well, roads are safe for all travellers. What’s missing is equivalent guidance for streets: routes that are designed to have a high level of interaction with the surrounding environment and usually lots of interactions between modes. Along streets, there is a common and constant desire for people to cross, whether it’s to access a business, bus stop, or residence. Streets are intentionally lined with things that people want to go to – that is their fundamental purpose.

Taking guidance developed for roads and applying it to streets is simply poor planning and engineering. It’s also partially how we’ve ended up with so many stroads; we build a road and then allow development along it that encourages lots of traffic and crossings, while simultaneously applying rigid rules about adding more crossings.

The Solution: New Guidance for “Streets”

What’s missing is guidance for traffic signals that is specifically catered to streets. Until recently, we haven’t even had the words to describe the difference between a road and a street. We have folks like Charles Marohn of Strong Towns to thank for popularizing this distinction. And now that we have the words for it, it’s time to put them into practice in engineering design guidance. Here’s what that could look like:

- Require municipalities, through their transportation master plans (TMP’s), to differentiate “roads” and “streets” in their networks. The City of Ottawa is an example of a municipality to have started this process in its ongoing TMP update; the City’s policy includes a distinction between “flow” and “access” oriented streets[3].

- Set high-level planning requirements for “roads” and “streets”. Any route designated as a “road” must have strict standards for how development can occur along it. Any route designated as a “street” may support a wider range of development, but must also be designed for safe access to those developments, meaning slower speeds, less travel lanes, and more crossing opportunities.

- Rather than requiring each crossing to “justify itself”, require that any designated “street” have a safe crossing on average every 200 metres by default, while allowing crossings spaced as little as 100 metres apart.

- Keep the existing warrant-based process for “roads”, since these routes are intended to prioritize car traffic and should be built without the features that encourage midblock crossings.

Coincidentally, Ontario just released a multi-modal level of service (MMLOS) guideline that assigns a pedestrian score of “F” for streets where the maximum distance between controlled crossings exceeds 320m. By this metric, just about every suburban arterial in Ontario is “failing” pedestrians today, and an engineer who wishes to resolve this faces an uphill battle against established guidelines.

With pedestrian injuries and fatalities continuing to mount on our roadways, combined with a wider policy interest in creating walkable suburbs, the time is now for changes to our engineering guidance around pedestrian crossings.

Notes

[1] The Transportation Association of Canada’s Pedestrian Crossing Control Guide (PCCG), Figure 8 (Decision Support Tool – Preliminary Assessment) allows crossings to be warranted if they are greater than “d” distance from the nearest control device, where “d” is between 100 and 200 metres and set by the local jurisdiction.

[2] The Region of Peel’s 2013 Road Characterization Study (PDF page 148) states that reducing the distance between intersections has been found to improve traffic performance on the main street because it allows some traffic to use parallel streets and reduces the peak load off the busiest intersections.

[3] The City of Ottawa’s policy distinction for “flow” and “access” roads started with its now-completed Official Plan update, enshrining these principles into the highest-level policy document. The TMP stops short of actually classifying streets as distinctly “flow” or “access” though, and reserves this for a future exercise, meaning “stroads” will continue to exist for the foreseeable future.

Jaywalking on the Bells Corners stroad https://bellscorners.wordpress.com/2017/08/18/jaywalking-riflemen-and-coyotes/

LikeLike