The ongoing pandemic and resulting shift of downtown office jobs to work-from-home is the final straw for the park-and-ride transit system. Now is the time to repurpose these public assets to save transit ridership and improve the well-being of our communities.

The park-and-ride was born of an age of narrow-minded, car-centric thinking. In the early days of urban sprawl when people first started moving beyond city centres, many jobs still remained in the central business districts (CBDs) located downtown. This presented a problem to the car-oriented vision of the future: building enough highway capacity and parking infrastructure for people to drive to their downtown jobs would result in the destruction of downtown itself. This didn’t stop some cities from pursuing this reckless goal, but for others, a new idea emerged.

Transit was reincarnated, albeit for a limited objective. Fast, long-distance commuter train and bus routes were built to connect downtown to the new low-density residential suburbs in Toronto, the Bay Area, Washington DC, Seattle, Atlanta, and many other cities. These new commuter services would provide the ultimate level of service for the suburban motorists, with plentiful, free parking surrounding each station. Whereas the train stations of the past were integrated into the fabric of the communities that they served, this era of train stations were relegated to industrial areas where land was cheap and undesirable for other uses.

A Flawed Design

This presents not only a flaw in the model of getting to transit, but in the design of the transit service itself. This narrow-minded thinking has resulted in trains and buses that are jam-packed heading downtown in the morning and back in the evening, but run near-empty at all other times of the day. Once a park-and-ride lot fills up in the morning rush, there is simply no more capacity for anyone else to drive there, even if there’s plenty of space on the trains and buses. Outside peak hours, the station, not the service, is the bottleneck that constrains transit ridership.

These transit agencies over time have become dependent on the downtown office commuter for their fare revenues. To create new ridership, transit planners execute the only tool that is tried and proven to work, time and again: building more parking. The cycle is self-reinforcing: building more parking generates more riders in the short term, but further increases the system’s dependency on creating more parking as the only means of getting new riders.

And the cycle has spun out of control. GO Transit, the operator of commuter rail service for the Greater Toronto Area, has a total of over 70,000 parking spaces at its stations – that’s more than four LA Dodger Stadium’s worth of parking!

The park-and-ride is also a problematic public asset because it privileges the wealthy. A commuter on the GO Train whose household makes more than $125,000 per year is nearly twice as likely to drive to the station compared to someone with a household income of less than $40,000 per year*. When parking is free, the cost to build, operate, and maintain it is bundled into the cost of the transit fare. In other words, when park-and-ride is free, the poorer riders subsidize the wealthier ones.

Enter COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the true vulnerability of this ridership growth strategy. The loss of the downtown office commuter due to the ongoing (and potentially long-term) practice of working from home has decimated transit agencies. Expansive parking lots and expensive parking garages that once overflowed with motor vehicle traffic now sit empty.

With many large firms announcing permanent or long-term shifts to working from home, it’s possible that volumes of downtown commuter trips may never return to their pre-pandemic levels. In other words, the “bread-and-butter” customer of many transit agencies is gone and may never come back. Those customers that remain on transit are mostly essential service workers and are more likely to be women, non-white, and low-income who do not have access to a car.

What does this mean for major investments underway or planned for new transit networks? The Greater Toronto Area is implementing a $16 billion expansion of its GO Transit commuter rail system. The City of Ottawa is spending $4.6B on a major expansion of its LRT system. Both are heavily focused on the need to increase the systems’ capacities to serve more commuters in peak hours, and both are now a potential financial risk to cities: if these projects fail to generate their projected ridership volumes, they will collect less revenue and require more subsidy.

A New Beginning

But the loss of the downtown office worker does not equate to the death of transit. People are still traveling and will always need to travel, and transit can serve these needs. People are still going shopping, visiting friends, and many do still need to get to jobs. Especially for essential service workers, a continued transit service is as important as ever, not just for them, but for all consumers that depend on them being able to get to their jobs.

The question transit agencies should be asking is not “when will people start commuting downtown again?”, but rather “how can we provide a transit service that is resilient to changing travel patterns?” Transit providers need to pivot their business models to serve multiple types of trips, by reimagining what the transit station itself and the surrounding area looks like. Failing to capture new trip types will lead to more people driving, something our vehicle networks (and climate change targets) cannot handle.

Repurpose the Park-and-Ride

The park-and-ride is the crux of the downtown commuter-based transit system. Wealthy office workers in the suburbs flock to free parking lots in the mornings from Monday to Friday, but otherwise ignore transit. The disappearance of these commuters means the loss of the park-and-ride’s value.

But seen in a different light, the park-and-ride system presents an incredible opportunity: land. Swaths of publicly-owned land, right next to high-frequency, long-distance transit services that connect across regions. Land that can be put to new and better use to create actual communities, rather than industrial parking deserts.

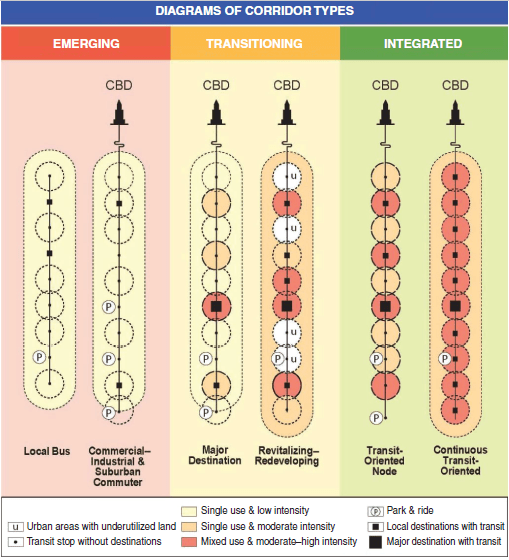

A 2017 academic study in the US compared and classified transit corridors with varying levels of development around each station. On the left are emerging transit corridors: those that that are almost entirely focused on the downtown commuter. Stations are surrounded by single-use, sprawled development, with lots of park-and-rides. On the other side, the integrated corridors feature high-intensity, mixed-use development around every station with very limited parking around stations.

and Land Use Integration by Bruce Appleyard, Christopher E. Ferrell, and Matthew Taecker

They found that compared to “emerging” corridors, these “integrated” corridors featured:

- More balanced, bidirectional ridership: people commute both ways on the network, which better utilizes the capacity of the transit service and puts less pressure on continuously increasing service in one direction

- 4x higher use of walking, biking, and transit: people living near stations on integrated corridors had significantly higher use of non-driving modes

- Less personal vehicle use: people living in integrated corridors drive, on average, a whopping 10,000 km less per year compared to people in emerging corridors

- 50 percent more trips to destinations within the corridor: people are more likely to travel along the corridor for multiple trip types, rather than just commuting.

Compared to the single-use, single-purpose nature of the park-and-ride commuter rail service, the integrated corridor supports multiple aspects of people’s lives, while diversifying transit use – a win-win for both the public and transit agencies.

Eggs in One Basket?

This is a simple exercise in risk management. Would you rather invest all of your life savings in a single company, or in a mutual fund that includes several hundred? For years transit agencies have been investing the savings of cities into the downtown commuter and the returns have been acceptable. But now that’s changed and the future is uncertain. The risk exposure of doubling down on this trip type has been exposed and agencies are suffering to attract riders. By moving away from a sole focus on the downtown commuter, transit agencies can diversify their investments and become more resilient.

The low-hanging fruit in all of this is the park-and-ride. In a matter of a few years this land could be transformed from asphalt deserts to vibrant communities with publicly-owned housing, shops, malls, schools, parks, and so much more all the while making transit stronger.

The downtown commuter has ditched transit; it’s time for transit agencies to ditch the park-and-ride.

*Source: Transportation Tomorrow Survey, 2016

1 Comment